↑

Freidrich Kittler, There is No Software, 1995

The bulk of written texts do not exist anymore in perceivable time and space but in a computer memory's transistor cells. And since these cells in the last three decades have shrunk to spatial extensions below one micrometer, our writing may well be defined by a self-similarity of letters over some six decades. This state of affairs makes not only a difference to history when, at its alphabetical beginning, a camel and its Hebraic letter gemel were just 2.5 decades apart, it also seems to hide the very act of writing: we do not write anymore. This crazy kind of software engineering suffered from an incurable confusion between use and mention. Up to Hölderlin's time, a mere mention of lightning seemed to have been sufficient evidence of its possible poetic use. After this lightning's metamorphosis into electricity, human-made writing passes through microscopically written inscriptions which, in contrast to all historical writing tools, are able to read and write by themselves. The last historical act of writing may well have been the moment when, in the early seventies, Intel engineers laid out some dozen square meters of blueprint paper (64 square meters, in the case of the later 8086) in order to design the hardware architecture of their first integrated microprocessor. This manual layout of two thousand transistors and their interconnections was then miniaturized to the size of an actual chip, and, by electro-optical machines, written into silicon layers. Finally, this 4004 microprocessor found its place in the new desk calculators of Intel's Japanese customer and our postmodern writing scene began.

Programming languages have eroded the monopoly of ordinary language and grown into a new hierarchy of their own. This postmodern tower of Babel reaches from simple operation codes whose linguistic extension is still a hardware configuration passing through an assembler whose extension is that very assembler. As a consequence, far reaching chains of self-similarities in the sense defined by fractal theory organize the software as well as the hardware of every writing. What remains a problem is only the realization of these layers which, just as modern media technologies in general, have been explicitly contrived in order to evade all perception. We simply do not know what our writing does.

In order to wordprocess a text and, that is, to become yourself a machine working on an IBM under Microsoft DOS, you need first of all to buy some commercial programs. At the one hand, they bear grandiloquent names such as WordPerfect, on the other hand, they bear a more or less cryptic (because non-vocalized) acronym such as WP. The full name, alas, serves only the advertising strategies of software manufacturers, since DOS as a microprocessor operating system could never read file names longer than eight letters. That is why the unpronounceable acronym WP, this posthistoric revocation of a fundamental Greek innovation, is not only necessary, but amply sufficient for postmodern wordprocessing. Surely, tapping the letter sequence of "W", "P" and "enter" on a keyboard does not make the Word perfect, but this simple writing act starts the actual execution of WordPerfect. Such are the triumphs of software.

In fact, however, these actions of agent WP are virtual ones, since each of them has to run under DOS. It is the operating system and, more precisely, its command shell that scans the keyboard for eight bit file names on the input line, transforms some relative addresses of an eventually retrieved file into absolute ones, loads this new version from external mass memory to the necessary random access space, and finally (or temporarily) passes execution to WordPerfect.

The same argument would hold against DOS which, in the final analysis, resolves into an extension of the basic input and output system called BIOS. Not only no program, but no underlying microprocessor system could ever start without the rather incredible autobooting faculty of some elementary functions that, for safety's sake, are burned into silicon and thus form part of the hardware. Any transformation of matter from entropy to information, from a million sleeping transistors into differences between electronic potentials, necessarily presupposes a material event called "reset".

In principle, this kind of descent from software to hardware, from higher to lower levels of observation, could be continued over more and more decades. All code operations, despite their metaphoric faculties such as "call" or "return", come down to absolutely local string manipulations and that is, I am afraid, to signifiers of voltage differences. Formalization in Hilbert's sense does away with theory itself, insofar as "the theory is no longer a system of meaningful propositions, but one of sentences as sequences of words, which are in turn sequences of letters. We can tell [say] by reference to the form alone which combinations of the words are sentences, which sentences are axioms, and which sentences follow as immediate consequences of others."

When meanings come down to sentences, sentences to words, and words to letters, there is no software at all. Rather, there would be no software if computer systems were not surrounded any longer by an environment of everyday languages. This environment, however, since a famous and twofold Greek invention, consists of letters and coins, of books and bucks. For these good economical reasons, nobody seems to have inherited the humility of Alan Turing, who, in the stone age of computing, preferred to read his machine's output in hexadecimal numbers rather than in decimal ones. On the contrary, the so-called philosophy of the computer community tends to systematically obscure hardware by software, electronic signifiers by interfaces between formal and everyday languages.

Firstly, on an intentionally superficial level, perfect graphic user interfaces, since they dispense with writing itself, hide a whole machine from its users. Secondly, on the microscopic level of hardware itself, so-called protection software has been implemented in order to prevent "untrusted programs" or "untrusted users" from any access to the operating system's kernel and input/output channels.

Precisely because software does not exist as a machine-independent faculty, software as a commercial or American medium insists all the more. In the USA, notwithstanding all mathematical tradition, even a copyright claim for algorithms has recently succeeded. At most, finally, there has been, on the part of IBM, research on a mathematical formula that would enable them to measure the distance in complexity between an algorithm and its output.

Under these tragic conditions, the criminal law, at least in Germany, has recently abandoned the very concept of software as a mental property; instead, it defined software as a necessarily material thing. The high court's reasoning, according to which without the correspondent electrical charges in silicon circuitry no computer program would ever run1, can already illustrate the fact that the virtual undecidability between software and hardware follows by no means, as system theorists would probably like to believe, from a simple variation of observation points. On the contrary, there are good grounds to assume the indispensability and, consequently, the priority of hardware in general. Only in Turing's paper "On Computable Numbers With An Application to the Entscheidungsproblem" did there exist a machine with unbounded resources in space and time, with infinite supply of raw paper and no constraints on computation speed. All physically feasible machines, in contrast, are limited by these parameters in their very code.

Software, if it existed, would just be a billion dollar deal based on the cheapest elements on earth. For, in their combination on chip, silicon and its oxide provide for perfect hardware architectures. That is to say that the millions of basic elements work under almost the same physical conditions, especially as regards the most critical, namely temperature dependent degradations, and yet, electrically, all of them are highly isolated from each other.

This structural difference can be easily illustrated. "A combination lock," for instance, "is a finite automaton, but it is not ordinarily decomposable into a base set of elementary-type components that can be reconfigured to simulate an arbitrary physical system. As a consequence it is not structurally programmable, and in this case it is effectively programmable only in the limited sense that its state can be set for achieving a limited class of behaviours." On the contrary, "a digital computer used to simulate a combination lock is structurally programmable since the behaviour is achieved by synthesizing it from a canonical set of primitive switching components."

↑

Jasbir Puar, Queer Times, Terrorist Assemblages, 2007

These are queer times indeed. The war on terror is an assemblage hooked into an array of enduring modernist paradigms (civilizing teleologies, orientalisms, xenophobia, militarization, border anxieties) and postmodernist eruptions (suicide bombers, biometric surveillance strategies, emergent corporealities, counterterrorism gone overboard). With its emphases on bodies, desires, pleasures, tactility, rhythms, echoes, textures, deaths, morbidity, torture, pain, sensation, and punishment, our necropolitical present-future deems it imperative to rearticulate what queer theory and studies of sexuality have to say about the metatheories and the “realpolitiks” of Empire. Queer times require even queerer modalities of thought, analysis, creativity, and expression in order to elaborate on nationalist, patriotic, and terrorist formations and their intertwined forms of racialized perverse sexualities and gender dysphorias.

I allude to queer praxis of futurity that insistently disentangle the relations between representation and affect, and propose queerness as not an identity nor an anti-identity, but an assemblage that is spatially and temporally contingent. The limitations of intersectional identitarian models emerge progressively—however queer they may be—as I work through the concepts of affect, tactility, and ontology. While dismantling the representational mandates of visibility identity politics that feed narratives of sexual exceptionalism, affective analyses can approach queernesses that are unknown or not cogently knowable, that are in the midst of becoming, that do not immediately and visibly signal themselves as insurgent, oppositional, or transcendent. This shift forces us to ask not only what terrorist corporealities mean or signify, but more insistently, what do they do? In this conclusion, I review these tensions between affect and representation, identity and assemblage, posing the problematics of nationalist and terrorist formations as central challenges to transnational queer cultural and feminist studies.

I propose the assemblage as a pertinent political and theoretical frame within societies of control. I rearticulate terrorist bodies, in particular the suicide bomber, as an assemblage that resists queerness-as-sexual-identity (or anti-identity)—in other words, intersectional and identitarian paradigms—in favor of spatial, temporal, and corporeal convergences, implosions, and rearrangements. Queerness as an assemblage moves away from excavation work, deprivileges a binary opposition between queer and notqueer subjects, and, instead of retaining queerness exclusively as dissenting, resistant, and alternative (all of which queerness importantly is and does), it underscores contingency and complicity with dominant formations. This foregrounding of assemblage enables attention to ontology in tandem with epistemology, affect in conjunction with representational economies, within which bodies interpenetrate, swirl together, and transmit affects and effects to each other.

The "affective turn" in recent poststructuralist scholarship indicates, I believe, that no matter how intersectional our models of subjectivity, no matter how attuned to locational politics of space, place, and scale, these formulations may still limit us if they presume the automatic primacy and singularity of the disciplinary subject and its identitarian interpellation. Patricia Clough has recently anointed this resurgence of interest in affect in poststructuralist inquiry the ‘‘affective turn,’’ marked by the spheres of technoscience criticism (Massumi, Hardt, Hardt and Negri, Clough, Parisi, De Landa) and queer theory on emotions and tactile knowings (Muñoz, Ahmed, Sedgwick, Cvetkovich). While reflective of the effects of poststructuralist exhaustion with representational analyses—in both Spivakian senses of portrait (Darstellung) and proxy (Vertreten)—an interesting split genealogy is emerging in these efforts. There are those writers who deploy affect as a particular reflection of or attachment to ‘‘structures of being’’ or feeling (per Raymond Williams; that is, a state prior to interpellation) that otherwise remains unarticulatable. In many cases affect in these works is situated in a continuum or becomes interchangeable with emotion, feeling, expressive sentiment (‘‘gay shame’’ is one such overdetermined fixation). The other genealogy we can point to is situated within a Deleuzian frame, whereby affect is a physiological and biological phenomenon, signaling why bodily matter matters, what escapes or remains outside of the discursively structured and thus commodity forms of emotion, of feeling. Brian Massumi, for example, posits affect as what escapes our attention, as what haunts the representational realm rather than merely infusing it with emotive presence. He regards affect in terms of ontological emergence that is released from cognition, codified emotion being the evidence of the escaped excess that is affect.

We must encourage genealogies of sexuality that suspend, for a moment, the rubrics of desire, pleasure, erotics, and identity that typically subtend ‘‘sex acts,’’ yet simultaneously avoid collapsing sexuality into a thin biopolitical frame of reproduction, hetero or homo. For if race and sex are to be increasingly thought outside the parameters of identity as assemblages, as events, what is at stake in terms of biopolitical capacity is therefore not the ability to reproduce, but the capacity to regenerate, the terms of which are found in all sorts of registers beyond heteronormative reproduction. The child is just one such figure in a spectrum of statistical chances that suggest health, vitality, capacity, fertility, ‘‘market virility,’’ and so on. For queer politics, the challenge is not so much to refuse a future through the repudiation of reproductive futurity, what Edelman hails as the reclamation and embracing of ‘‘No Future’’ that he claims is always already attached to gay bodies, but to understand how the biopolitics of regenerative capacity already demarcate racialized and sexualized statistical population aggregates as those in decay, destined for no future, based not upon whether they can or cannot reproduce children but on what capacities they can and cannot regenerate and what kinds of assemblages they compel, repel, spur, deflate.

As opposed to an intersectional model of identity, which presumes that components—race, class, gender, sexuality, nation, age, religion—are separable analytics and can thus be disassembled, an assemblage is more attuned to interwoven forces that merge and dissipate time, space, and body against linearity, coherency, and permanency. Intersectionality demands the knowing, naming, and thus stabilizing of identity across space and time, relying on the logic of equivalence and analogy between various axes of identity and generating narratives of progress that deny the fictive and performative aspects of identification: you become an identity, yes, but also timelessness works to consolidate the fiction of a seamless stable identity in every space. Furthermore, the study of intersectional identities often involves taking imbricated identities apart one by one to see how they influence each other, a process that betrays the founding impulse of intersectionality, that identities cannot so easily be cleaved. We can think of intersectionality as a hermeneutic of positionality that seeks to account for locality, specificity, placement, junctions. As a tool of diversity management and a mantra of liberal multiculturalism, intersectionality colludes with the disciplinary apparatus of the state—census, demography, racial profiling, surveillance—in that ‘‘difference’’ is encased within a structural container that simply wishes the messiness of identity into a formulaic grid, producing analogies in its wake and engendering what Massumi names ‘‘gridlock’’: a ‘‘box[ing] into its site on the culture map.’’

Terrorist assemblages not only counter sexual exceptionalisms by reclaiming contagion—the nonexceptional—within the gaze of national security. In the commingling of queer monstrosity and queer modernity, they also creatively, powerfully, and unexpectedly scramble the terrain of the political within organizing and intellectual projects, weakening the tenuous collusion of the disciplinary subject and the population for control. We cannot know assemblages in advance, thus taunting the temporal suffocation plaguing identity politics to which Chow draws our attention. Displacing visibility politics as a primary concern of queer social movements, assemblages demonstrate the import of theorizing the queer affective economies that impact and engrave but also announce, trail, and emblazon queer bodies: suicide bombers, the turbaned Sikh man, the monster-terrorist-fag, the tortured Muslim body, the burqa’ed woman, the South Asian diasporic drag queen, to name a few. These terrorist assemblages, a cacophony of informational flows, energetic intensities, bodies, and practices that undermine coherent identity and even queer anti-identity narratives, bypass entirely the Foucauldian ‘‘act to identity’’ continuum that informs much global lgbtiq organizing, a continuum that privileges the pole of identity as the evolved form of western modernity. Yet reclaiming the nonexceptional is only partially the point, for assemblages allow for complicities of privilege and the production of new normativities even as they cannot anticipate spaces and moments of resistance, resistance that is not primarily characterized by oppositional stances, but includes frictional forces, discomfiting encounters, and spurts of unsynchronized delinquency (the jamming of technological and informational infrastructures such as underground hacker subterfuge, viruses, mobile models of crowd gathering at antiwar protests). These unknowable terrorist assemblages are not casual bystanders or parasites; the nation assimilates the effusive discomfort of the unknowability of these bodies, thus affectively producing new normativities and exceptionalisms through the cataloguing of unknowables. Opening up to the fantastical wonders of futurity, therefore, is the most powerful of political and critical strategies, whether it is through assemblage or to something as yet unknown, perhaps even forever unknowable.

↑

Wu Ming, Selected Interviews

Q. Does Wu Ming represent "the death of the author"? Are you saying that the name of the writer is not important because what's important are the multimedia narratives created by the multiple entities behind the same pen name? Where does this stance put Wu Ming in the ongoing battles over copyright?

A. I'm not particularly interested in the debate on the death of the author. I don't bear any grudge against authors in and of themselves. We're authors ourselves. However, we believe that the author is overrated. There's too much bad rhetoric around the author. Some of those people are too full of themselves, and there's a whole system thriving on their being full of themselves, and on the public contemplating in awe their selfish attitude. Authors have no supernatural powers. Quite a few of them don't even have anything to say. Their only asset is that they know how not to say it. They have the language to say nothing at all and be praised about it. As for the copyright battle—it is no mystery that all our books are freely reproducible, they can be downloaded from our Web site, and people can distribute them in any way they please, as long as distribution remains free and they don't ask for any money. If they make money, we want a slice of the cake.

Q. 'It's the economy, stupid!' What are your thoughts about the current cultural situation, both in a national, European and global context?

A. The complete failure of the neo-liberal economics pushed by the IMF and the WTO is under everyone's eyes. Capital devised two main "solutions" to the 1929 Wall Street Crack and the 1930's Depression: one was Roosevelt's New Deal, the other one was Fascism. So far, the answer to the current global crisis is no new deal, it is warfare. The Neo-Con gang (which includes Tony Blair) has declared war on the planet but nobody can win a war on the whole planet, also because the US are a gradually declining superpower, not the Romulan empire. The inevitable "Vietnamization" of the Middle East shouldn't have taken anyone by surprise, it is only natural. More and more soldiers will die, by the end of 2004 we'll have counted them by the thousands. We're not happy about it but it shows that anti-war movements were right, that "pre-emptive war" was going to be a catastrophic adventure. The point is that the powers-that-be are nihilist, they don't give a shit about the future, they just want power and profits now. If not so, why don't they care about global warming instead of waging absurd wars? Why don't they care about power outrages instead of trying to fool us into thinking that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction?

Q. After the protests in Genoa in 2001, you described the event as a “crucial moment for the latest generation of activists” and talked about how it contributed to the understanding that you cannot “besiege a power that is everywhere” – the realization that capitalism’s power lies in the fact that it does not reside in a single place (a castle, a conference hall etc) but has been incorporated into almost every aspect of our social and economic life. Can this criticism be easily applied to the Occupy Movement that has turned up at Wall Street – the formal home of our financial system – or do you think there are important differences?

A. Violating the “red zones” was pure self-delusion, there was nothing in there, actual decisions were not taken in those summits. Capitalist power isn’t inside any fortress: it is in the microphysics of daily exploitation, in financial exchanges, and so on. The Occupy Wall Street movement, which has now turned into the Occupy Everything movement, is already a step – maybe several steps – ahead. As McKenzie Wark wrote, they started by occupying an abstraction, they weren’t actually occupying Wall Street, they were occupying the concept of Wall Street, and the rhetorical device by which Wall Street had come to mean “financial capital”. There is a more precise insight on how power works. In Italy we had “Occupy Bank of Italy”: campers weren’t really occupying the bank, they were shifting the focus of public discussion from Burlesquoni’s theatrical antics to the austerity measures dictated to Italy by the European Central Bank. They chose Banca d’Italia as a target because that was Mario Draghi’s last week as governor of the Bank. He was going to become president of the ECB. The movement was attacking enemy troops not in the positions they were leaving, but in the positions they were about to take possess of. In short, there were no trivialities like “Let’s besiege the palaces of power.”

↑

Peter Sloterdijk, Cell Block, Egospheres, Self-Container, 2007

Those who study the history of modern architecture in relation to the forms of life found in a mediatized society will immediately realize that the two most successful architectural innovations of the 20th century - the apartment and the sports stadium - are directly related to the two most prevalent sociopsychological tendencies of this epoch: the setting free of solitary individuals with the help of individualized home and media technologies, and the aggregation of masses, unified in their excitement, with the help of staged events held in "fascinogenic” mass structures. For now, we will not emphasize that the affective and imaginary synthesis of modern society is more likely to take place through mass media - that is, through the telecommunicative integration of nonassembled people - than through physical assembly; meanwhile, the operative synthesis of society is more likely to organize itself through market relationship.

The modern apartment, or that which is referred to as a studio or one-room apartment - is the material realization of a tendency toward cell-formation, which can be recognized as the architectural and topological analogue of the individualism of modern society. As to the meaning of these individualistic aspirations, we will content ourselves for the moment with an observation that Gabriel Tarde already made in the 1880s: "Today's civilized person is really aspiring to the possibility of dispensing with human support." One can also read, in the evolution of apartment construction, that nothing is less based on presuppositions than the seemingly natural expectation that there should be at least one room for every person, or one living unit per head. Just as Soviet modernism was condensed into the myth of the communal apartment, which was to be the press that would mint a New Man fit for the collective, so too does Western modernism gather itself under the myth of the apartment, where the liberated individual, who has been made flexible by flows of capital, devotes himself to the cultivation of his relationship to himself.

We will define the apartment as an atomic or elementary "egospheric" form - as a cellular world-bubble, the massive repetition of which generates individualistic foams. There is no moral judgment tied to this conclusion; it contains no concessions to current catholic and neoconservative criticism that, in its discussion of the contemporary trend toward "singles culture," offers little more than a stereotypically Augustinián scolding of egoism and indifference. The only new thing offered is the pointed remark that the modern egoist has started subscribing to the Daily Me. We will also keep our distance when terms like Existenzminimum are brought into play.

To get closer to understanding the phenomenon of the apartment, one must take note of its close alliance with the principle of seriality, without which the crossing over of building (and manufacturing) into the age of mass- and pre-fabrication could not be imagined. Just as, according to El Lissitzky, constructivism represented the transfer point between painting and architecture, so too does serialism represent the transfer point between elementarism and social utopianism. In serialism - which regulates the relationship between part and whole through precise standardization, so that decentralized fabrication and centralized installation become possible - lies the key to the relationship between cell and cellular compound. Just as the composition of the cell, by fully returning to the elementary level, accommodates itself to analytical thinking, so does the building of houses on the basis of these elements suggest a combinatorics - or better, a form of "organic construction" - with the goal of generating architecturally, urbanistically, and economically tenable ensembles out of modules.

The semblance of individualism, which in modernism was supposed to harden into an ontology of separateness, could not become truly suggestive until today's media revolution had run its course. Ego-technological media in particular contributed to this by inscribing the individual with new routines and methods of returning to the self. In the first line are the writing and reading technologies with whose help historically unprecedented kinds of procedures of inner dialogue, and of self-examination and self-documentation, have become habituated. Consequently, the homo alphabeticus did not just develop the characteristic practice of self-objectification, but also the practice of reuniting with oneself by appropriating the objectified. The diary is one such ego-technological form; soul-searching is another. In my thinking on the history of human faciality in general, and European interfacial relations in particular, I referred to the recent and incisive introduction of the mirror into the optical self-relationship of Europeans, and emphasized the contribution of this paradigmatic, ego-technological device in the transition from sensual reflection in the other to so-called self-reflection. In the everyday routine of the modern apartment resident, just as in that of his contemporaries, the glance in the mirror has become a regular practice that serves his ongoing self-adjustment

This presupposes the individual's unrelenting self-observation of any metabolic and aggregative change in all of its dimensions. Individualism is a cult of digestion that celebrates the passage of foods, experiences, and information through the subject. As all is immanence, the apartment becomes an integral toilette: everything that happens here is under the premise of end use in every respect. Eating/ digesting; reading/writing; watching television/opining (Meinen"); self- recovery/self-engagement; self-arousal/self release. As a micro theater of autosymbiosis the apartment sheathes the existence of individuals who apply for experience and significance. As it is simultaneously a cave and a stage, the apartment as much provides accompaniment for the debut of the individual as it does for his return back into irrelevance. One can illustrate this with the typical stations of the self-care cycle, through which the apartment's subject moves as he follows his daily script. It begins with the morning toilet, which consists of voiding, washing, cosmetic allowances, and dressing. Cosmetic autopraxis already offers, at a relatively simple level, a universe of differences that are given great intrinsic value by their users. Through cosmetics, one's own facial countenance - the appearance - can near the level of the artwork. Similarly, the choice of clothing for its part encompasses many micro universes of nuances and gestures; here the outfit becomes a design problem, and the clothing choices a self-project. In fact, in a developed "experience" society the individual qualifies as an author who claims authorship of his own image. The individual determines the psychosocial revenues of his clothing strategy by the direct and indirect successes of his appearances.

With good reason it has been claimed that postmodernism is a by-product of remote control. The telecommander represents the key technology for the control of sound and image input, and eo ipso of reality admittance into the egosphere. Considering that a creature of the homo sapiens type becomes that which it hears, the transition to an individual having the option to self-tune presents an anthropological juncture: involuntary outer hearing, like involuntary inner hearing, of which psychoanalysis offered a partial transcription with the term superego (which concerned the moralistic aspect of the individual being outvoiced by the collective), dissolves in the trend toward the choice of one's own auditory environment. Of course there will always be layers of inner and outer hearing in which involuntarily heard sounds enter into voluntary hearing, even in the individual phonotop.

Only the telephone can rival the significance of audio media in the atmospheric framing of the egosphere - and represents, without saying, one of the most effective means of connecting the reserve of the apartment to the world because of its quality as a two-way medium. In contrast to even the latest one-way media (radio, TV, newspaper, books), the telephone possesses a double ontological privilege: it not only transmits calls from (usually) the Real, it also brings the one being called, provided that he picks up, into an (actually experienced) synchronicity with the caller - on the same level of being as the placer of the call from afar. Because of this effect of immediacy, it is legitimate to describe the telephone as a biophone - anything less than a life cannot make a call. Somebody on the phone - this is always a distant life made present, a voice with a message, maybe even an invitation. Because it can be reached with a phone call, the apartment loses its "unity of place" as it is, in turn, connected to a network of virtual neighborhoods. The neighborhood then becomes, in effect, not a spatial one, but a telephonic one. From an immunological point of view the telephone represents a more ambivalent recent arrival, because it introduces apotential canal for risky infections from the outside into the living cell, but at the same time explosively stretches out the radius of the inhabitant in the sense of expanded alliances and opportunities for agency (the Internet does not have to be the focal point in this context because, for the time being, it only offers the continuation of the telephone by visual means). After writing had already dissolved the synchronicity of communication, the telephone also abolished the need for having to be in the same place.

In no other dimension of life does this make itself so obvious as with sexuality, which in the individualistic regime is often set up as an apartment-based sexuality of "experience," or, respectively, as research into an inner erotic space of possibilities. Clearly, the transition to so-called liberated sexuality in the second half of the 20th century is inextricably tied to the privacy gained by the discretion of apartment culture, or at least the safety of one's own room. The overanalyzed phenomenon of biochemical contraceptives, which have been available to women, married or not, since the 1960s, only confirms the fact that the manifestrend since the 1920s has been toward an affirmation of solitary eroticism. The apartment forms a miniature erototof in which singles can pursue their impulsive desires in the sense of also-wanting-to-experience-what-others-have-alreadyexperienced. It represents an exemplary backdrop for existence because in it a form of consumer relations can be practiced toward one's own sexual potential. But if the lover (erástes) and the beloved (e romenos ) fall within one and the same person, this centaur is not spared the elementary experience of all lovers, which is that the love object only rarely responds on the same wavelength.

In autoeroticism, as in its bipersonal counterpart, the same rule follows that when the need for choosing a partner arises, most are doomed to misfire. As the rule is that generally people do not get the one they really want, they replace them with someone else - in this case, with themselves. For this reason the apartment is also an atelier for dealing with frustrations - more specifically, a testing cell in which the desire for a real or imaginary opposite is transformed into a desire for oneself as the most plausible representative of the other one had one's sights on. In this paradoxical circle, a self-gratifying masturbation with offensive tendencies is developed. Apartment onanism, most likely prefigured in cloister cells, sets the stage for the complete three-figure relationship between the subject, the genitals, and the phantasma. It must be made clear, by the way, that even if masturbatory sexuality achieves a pragmatic abbreviation, it does not necessarily represent a structural simplification of an interpersonal bigenital operation. One can hence best explain the erototopic characteristics of the apartment with an analogy to the brothel: just as the suitors look around at the available sexual partners, and, after having come to an agreement, go to a rented cell with the object of their preference, so too the resident chooses himself as the closest other, and uses the seclusion of his living unit to get it on with himself. Self-pairing is carried out here with the nuance that the individual, without any formalities, makes advances toward himself as a self-suitor. This can, as a familiar example shows, even lead to a promotion by one's own grace.

The modern apartment cell takes on - aside from its chiro-, thermo-, and eroto- topic qualities - the characteristics of an ergotop the moment its inhabitant makes it the scene of his athletic self-care. This transformation from apartment to private gym is encouraged by modern society's trend toward fitness-oriented lifestyles, which demand that their adherents pay constant attention to their figures. From this point of view, the structure of self-pairing modifies itself so that the exercising individual splits himself into both the trainer and the trainee in order to unify both into a coordinated routine. Here, fixed or moveable training equipment can take over the manifest third role in the objective organization of a self-relationship. In other cases it is equipment-free exercises on the floor, with which a gymnastic monologue is carried out. Existentialism explicated itself somatically: based on the philosophical formula that being (Dasein) is the relationship that relates oneself to oneself, a new version has come onto the market, one that is more easily understood, according to which "being" means keepingoneself-in-shape.

Finally, the apartment can be described as the satellite station of the aletbotop (republic of knowledge). In every life, as much as it might be averted from the universal, there is a residual interest in truth, even if it is just in the demand for vocabulary that helps the individual to be plugged in to the signs of the times. He who demonstrates a moderate level of consumption of media generally attains the cognitive Existenzminimum that is customary for our current world form (Weltform), and is granted the license to vote and have one's voice be heard. Those who demand more strive for knowledge, which would enable them to orient themselves during extensive navigation in murky waters. In the self-relationship of the alethotop, individuals are informally employed as self-tutors who are responsible for sustaining a certain fit with the cognitive or scientific position of society; as minimal autodidacts they afford themselves an idiosyncratic share of the publicly available resources of the cognitive souci de soi . Even if it is true that learning, according to the current requirements of cognitive theory, can at most be interpreted as an enlightened management of ignorance, halfway discriminating contemporaries in so-called "knowledge societies" must at least put themselves to the task of constantly updating their deficiencies. From here on the point of positive information is above all to more realistically determine the scale of what is unknown or unclear. In addition, information increasingly gains a function that is in keeping with fashion and labels - one wears isolated particles of knowledge just as one wears sunglasses, expensive watches, and baseball caps. In Japanese youth culture a scene was started in the 1980s that was dedicated to the cult of senseless, specialized knowledge. These youths understood that knowledge does not prepare you for life, but for quiz shows.

Scene and fashion magazines usually serve as information sources for single inhabitants, in addition to nonfiction books that now and again get incorporated into the domestic collection. For many, the reception of a new book into the community of objects that populate the apartment is still an event. To the charm of life in an apartment belongs the fact that one can here, without any witnesses, dedicate oneself to the honest bookkeeping of the unique ignorances that are unmistakably one's own.

↑

Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, 2015

“The CIA can neither confirm nor deny the existence or nonexistence of records responsive to your request.” Sometime in the spring of 2011, I wrote to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to request the release of any documents pertaining to Frantz Fanon under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). He arrived in the United States on October 3, staying at a hotel in Washington, DC, where he was “left to rot,” according to Simone de Beauvoir, “alone and without medical attention.” I didn’t get any documents from the CIA except a letter citing Executive Order 13526 with the standard refrain that the agency “can neither confirm nor deny the existence or nonexistence of records,” and further stating that “the fact of the existence or nonexistence of requested records is currently and properly classified and is intelligence sources and methods information that is protected from disclosure. Document #105-96959-A, the news clipping, names The Wretched of the Earth (1963) as Fanon’s most important book describing Fanon as a “black intellectual,” a “radical revolutionary,” and “a philosophical disciple of Karl Marx and Jean Paul Sartre, [who] preached global revolt of the blacks against white colonial rule.”

During lectures Fanon put forth the idea that modernity can be characterized by the “mise en fiches de l’homme.” These are the records, files, time sheets, and identity documents that together form a biography, and sometimes an unauthorized one, of the modern subject. In a manner similar to the detailed case histories of colonial war and mental disorders found in the fifth chapter of The Wretched of the Earth, in a section of the notes on these lectures titled “Le contrôle et la surveillance” (in English “Surveillance and Control”), Fanon demonstrates his role as both psychiatrist and social theorist, by making observations, or social diagnoses, on the embodied effects and outcomes of surveillance practices on different categories of laborers when attempts are made by way of workforce supervision to reduce their labor to an automation: factory assembly line workers subjected to time management by punch clocks and time sheets, the eavesdropping done by telephone switchboard supervisors as they secretly listened in on calls in order to monitor the conversations of switchboard operators, and the effects of closed- circuit television (CCTV) surveillance on sales clerks in large department stores in the United States. This is control by quantification, as Fanon put it. The embodied psychic effects of surveillance that Fanon described include nervous tensions, insomnia, fatigue, accidents, lightheadedness, and less control over reflexes. Nightmares too: a train that departs and leaves one behind, or a gate closing, or a door that won’t open.

Dark Matters suggests that an understanding of the ontological conditions of blackness is integral to developing a general theory of surveillance and, in particular, racializing surveillance—when enactments of surveillance reify boundaries along racial lines, thereby reifying race, and where the outcome of this is often discriminatory and violent treatment. It is through this archive and that of black life after the Middle Passage that I want to further complicate understandings of surveillance by questioning how a realization of the conditions of blackness—the historical, the present, and the historical present—can help social theorists understand our contemporary conditions of surveillance. Put another way, rather than seeing surveillance as something inaugurated by new technologies, such as automated facial recognition or unmanned autonomous vehicles (or drones), to see it as ongoing is to insist that we factor in how racism and antiblackness undergird and sustain the intersecting surveillances of our present order. Surveillance is nothing new to black folks. It is the fact of antiblackness.

Dark Matters stems from a questioning of what would happen if some of the ideas occurring in the emerging field of surveillance studies were put into conversation with the enduring archive of transatlantic slavery and its afterlife, in this way making visible the many ways that race continues to structure surveillance practices. If we are to take transatlantic slavery as antecedent to contemporary surveillance technologies and practices as they concern inventories of ships’ cargo and the arrangement laid out in the stowage plan of the slave ship, biometric identification by branding the slave’s body with hot irons, slave markets and auction blocks as exercises of synoptic power where the many watched the few, slave passes and patrols, manumission papers and free badges, black codes and fugitive slave notices, it is to the archives, slave narratives, and often to black expressive practices, creative texts, and other efforts that we can look for moments of refusal and critique. Slave narratives, as Avery Gordon demonstrates, offer us “a sociology of slavery and freedom.”

Dark Matters seeks to make an intervention in the literature by naming the “absented presence” of blackness as part of that absence in the literature. In the sense that blackness is often absented from what is theorized and who is cited, it is ever present in the subjection of black motorists to a disproportionate number of traffic stops (driving while black), stop- and- frisk policing practices that subject black and Latino pedestrians in New York City and other urban spaces to just that, CCTV and urban renewal projects that displace those living in black city spaces, and mass incarceration in the United States where, for example, black men between the ages of twenty and twenty- four are imprisoned at a rate seven times higher than white men of that age group, and the various exclusions and other matters where blackness meets surveillance and then reveals the ongoing racisms of unfinished emancipation. Unfinished emancipation suggests that slavery matters and the archive of transatlantic slavery must be engaged if we are to create a surveillance studies that grapples with its constitutive genealogies, where the archive of slavery is taken up in a way that does not replicate the racial schema that spawned it and that it reproduced, but at the same time does not erase its violence.

If, for Foucault, “the disciplinary gaze of the Panopticon is the archetypical power of modernity,” then it is my contention that the slave ship too must be understood as an operation of the power of modernity, and as part of the violent regulation of blackness. I plot dark sousveillance as an imaginative place from which to mobilize a critique of racializing surveillance, a critique that takes form in anti-surveillance, counter-surveillance, and other freedom practices. Dark sousveillance, then, plots imaginaries that are oppositional and that are hopeful for another way of being. Dark sousveillance is a site of critique, as it speaks to black epistemologies of contending with antiblack surveillance, where the tools of social control in plantation surveillance or lantern laws in city spaces and beyond were appropriated, co-opted, repurposed, and challenged in order to facilitate survival and escape. Dark sousveillance is also a reading praxis for examining surveillance that allows for a questioning of how certain surveillance technologies installed during slavery to monitor and track blackness as property (for example, branding, the one- drop rule, quantitative plantation records that listed enslaved people alongside livestock and crops, slave passes, slave patrols, and runaway notices) anticipate the contemporary surveillance of racialized subjects, and it also provides a way to frame how the contemporary surveillance of the racial body might be contended with.

↑

DAAR, Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency, 2013

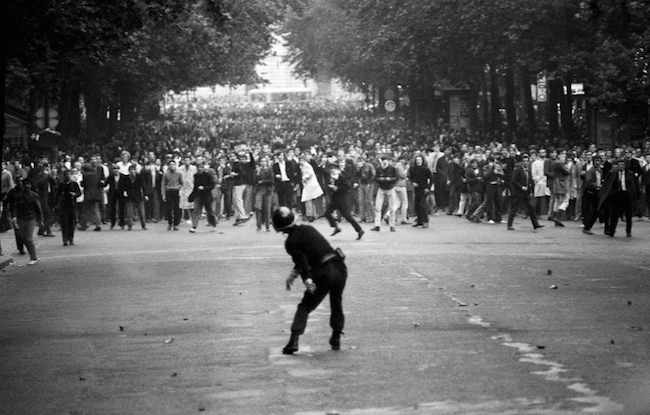

The army withdrawal seemed to have been the last act in an ongoing struggle of local and international activists against the oppressive presence of the base. Some years previously, on a legendary day, protesters broke into the military base and called for its immediate removal. The soldiers, taken completely by surprise, did nothing but watch. Relief gave way to cathartic release. Using iron bars, young people smashed windows, walls, and doors. others tried to salvage and take away whatever they could. The commotion was incredible, but nobody got hurt. This was the end of the long life of the site as a military outpost. The evacuation of the outpost was surely only a tactical move, a reorganization of the military matrix of control. No one was under any illusion that this might have been the first stage of decolonization. Still, “something” had taken place - a military base had been evacuated and people had access to it. This moment of evacuation - “nothing” in the grand scheme of things - captured our imagination as it had defied the logic of impossibility and the seemingly hard geography that is prevalent in occupied Palestine.

The access to the military base provided a new point of observation over the city itself. Its evacuation offered local people the opportunity to see their own city from this direction for the first time. For many, it was a strange feeling, similar to that of looking at a recording of oneself and discovering unknown aspects. Having access to the evacuated military base we experienced the most radical condition of architecture - the very moment that power has been unplugged: the old uses are gone, and new uses not yet defined. Only after such initial encounters can collective thinking about the future of this place begin.

If one insists, as we do, on colonization as the frame of reference for understanding the political reality in palestine, one should naturally accept that decolonization is necessary. The general conceptual question nonetheless remains: what is decolonization today? The current political language that utilizes the term “solution” in relation to the Palestinian conflict and its respective borders is similarly aimed at a fixed reality. “Decolonization,” however, is not bound as a concept, nor is it bound in space or in time: it is an ongoing practice of deactivation and reorientation understood both in its presence and its endlessness. Decolonization, in our understanding, seeks to unleash a process of open-ended transformation toward visions of equality and justice. The return of refugees, which we interpret as entailing the right to move and settle within the complete borders of Israel-Palestine, is fundamental in decolonization.

The philosopher Giorgio Agamben has been generous in engaging us in conversations about how the concept of “profanation” would be a productive way of thinking through the process of decolonization. In his book, Agamben points out that “to profane does not simply mean to abolish or cancel separations, but to learn to make new uses of them.” Might decolonization then be the counter-apparatus to restore to common use what the colonial order has separated and divided? Decolonization as an act of profanation is playful, child-like, and a necessary contrast against actions disposed towards the diverse manifestations of the contemporary sacred.

Zones of Palestine that have been or will be liberated from direct Israeli presence have produced a crucial laboratory for studying the multiple ways in which we could imagine the reuse, re-inhibition, or recycling of Israel’s colonial architecture. The popular impulse for destruction seeks to spatially articulare “liberation” from an architecture understood as a political straitjacket, an instrument of domination and control. If architecture is a weapon in a military arsenal that implements the power relations of colonialist ideologies, that architecture must burn. Frantz Fanon, pondering the possible corruption of governments after decolonization, warned during the Algerian liberation struggle, that if not destroyed, the physical and territorial reorganization of the colonial world may once again “mark out the lines on which a colonized society will be organized.” For Fanon, decolonization is always a violent event. “To destroy the colonial world means nothing less than demolishing the colonist's city, burying it deep with the earth or banishing it from the territory.”

The impulse of destruction seeks to turn time backward. It seeks to reverse development to its virgin nature, a tabula rasa on which a set of new beginnings might be articulated. However, time and its processes of transformation can never be simply reversed: rather than the desired Romantic ruralization of developed areas, destruction generates desolation and environmental damage that may last for decades. In 2005, Israel evacuated the Gaza settlements and destroyed three thousand homes, creating not the promised tabula rasa for a new beginning, but rather a million and a half tons of toxic rubble that poisoned the ground and water.

The other impulse, to reuse, seeks to impose political continuity and order under a new system of control. It is thus not surprising that post-colonial governments have tended to reuse the infrastructure set up by colonial regimes for their own emergent practice needs of administration. The reuse of Israeli colonial architecture could establish a sense of continuity rather than rupture and change. That is, ruining the evacuated structures of Israel’s domination in the same way as the occupiers did - the settlements as Palestinian suburbs and the military base for Palestinian security needs - would mean reproducing their inhere alienation and violence: the settlement’s system of fences and surveillance technologies would inevitably enable their seamless transformation into gated communities for the Palestinian elite.

There is, however a third option: a subversion of the original intended use, repurposing it for other ends. We know that evacuated colonial architecture doesn’t necessarily reproduce the functions for which it was designed. Even the most horrifying of structures of domination can yield themselves to new forms of life. Looking at the fractured remains of a plantation house, the Caribbean poet Derek Walcott pondered the decay of an institution once powerful, and wondered about “the rot that remains when the men are gone,” but he also opened ways to negotiate, inhabit, and thus transform the colonial structures that have generated deep deformations of space and geography. Colonial remnants and ruins are not only the dead matter of past power, but could be thought of as material for re-appropriation and strategic activation within the political of the present. The question is how people might live with and in ruins, or, “within the house of the enemy.”

The prisoner-of-war camp Fossoli di Carpi, northern Italy, was used as a concentration camp for Jews who were imprisoned there before their deportation to death camps in Eastern Europe. Two years after the end of the war the priest Zeno Saltini opened an orphanage there. The walls and barbed wire were pulled down, and the barracks were transformed into living quarters, a school, workshops. Trees, gardens, and vegetables were planted. The camp watchtower was transformed into a church.

Another interesting case was that of Staro Sajmište. Built as a fairground in 1936 it had a series of national pavilions built around a central tower. The area had fallen into Nazi hands at the start of World War II. The visual order of the exhibition suited the new logic of surveillance and control. After the way, the site was occupied by artists and Roma people. The circular layout of the camp has thus been interpreted in radically different fashions three times: as a display mechanism, a site of incarceration and murder, and then a site of renewed communal life.